Back To Bases With WealthScapes, A Guide To Denominator Selection

Generally, most geodemographic research is conducted at the household level. Consider a marketer who wants to target households with high mutual fund balances. To convert the raw WealthScapes data into an actionable statistic, the marketer would need to turn the aggregate mutual fund balance of the neighbourhood into an average statistic. While the numerator of this average statistic is the aggregate balance of the target product (in this case mutual funds), there are choices with respect to the proper denominator. For example, the denominator could be the average mutual fund balance per household (meaning all households, whether they own the product or not), or it could be the average mutual fund balance per holding household (defined as a household that either owns the asset or is the holder of the debt). Similarly, it could be just as reasonable to calculate the denominator based on the average mutual fund balance per investment holding household(households that own one or more investment products). All three statistics have merit and it is the responsibility of the analyst to determine the most appropriate denominator for the research at hand. With that challenge in mind, this blog has been written to guide the analyst in choosing the proper denominator.

Average Balance Per Household

The average balance per household is the best statistic to use about 90% of the time. Usually, marketers want to target spatially defined groups of households (i.e., neighbourhoods, postal codes, trade areas or cities). In order to compare multiple groups of households, the simplest approach is to imagine what the “average” household looks like. By dividing the aggregate balance by the total number of households, the average balance per household captures two separate effects at once: the propensity of households to hold this asset or liability and the average balance of those households that hold this asset or liability.

Here’s an example of a good case for using the average balance per household. A marketer wants to sell mutual funds to a neighbourhood and has determined the best prospects are those households that already hold mutual funds. The marketer’s goal is to sell the highest mutual fund balance (dollars). Assuming that the cost of targeting and response rate of a single household are fixed (constant), the marketer would target those neighbourhoods with the highest average balance per household first. Because the marketer cannot target those individual households with mutual funds, it is best to target neighbourhoods where the propensity to hold mutual funds is high, the typical average balance of mutual fund holders is high–or, preferably, both. Effectively, the average mutual fund balance per household has already made the requisite trade-off between high propensity and high balances in order to maximize expected revenues.

Average Balance Per Holding Household

The average balance per holding household is the best statistic to use about 10% of the time; typically when the marketer already has some information about the target audience (for example, a list of homeowners or clients who already hold investment products). This statistic is calculated by dividing the aggregate balance or value of the targeted product by the number of households which either hold this product or hold another appropriate product. This is a much more subtle statistic and generally takes one of two forms: the average balance per holding household of the targeted product or the average balance per holding household of another product. An example of the former is dividing the aggregate mutual fund balance by households who hold mutual funds, whereas an example of the later is dividing the aggregate mutual fund balance by households that hold one or more investment products (stocks, bonds and mutual funds). As the calculation implies, these statistics do not address the neighbourhood’s propensity to hold these products but rather only addresses the average balances of holders.

Continuing with the example developed previously, let’s say that the mutual fund marketer already has a collection of mutual fund holding customers in the target neighbourhood whose average mutual fund balance is, say, $40,000 per household. But the average balance per holding household in the neighbourhood is higher, say, $50,000. This means that either (a) the marketer’s clients likely have $10,000 on average in additional mutual fund holdings that can be targeted for conversion to the marketer’s company or (b) the marketer’s clients tend to have lower mutual fund balances than the average holding household in the neighbourhood. The truth is probably a mix of the two situations and it is the marketer’s role to determine (usually by corollary evidence) to what degree one explanation is more accurate than the other. If the marketer decides that (a) is the likely cause of the deviation, then the marketer can target her or his clients with a conversion campaign to consolidate all of the mutual funds with the marketer’s firm. If (b) is true, then the marketer can fine tune a marketing message to the remaining households in the neighbourhood—perhaps extolling the virtues of the marketer’s more premium offerings.

Average Balance Per Investment Holding Household

Alternatively, one might consider a denominator that is not the product’s holdership count. Empirical evidence suggests that households can be put into one of two general classes: debtor households and investor households. An investor household would be a household that holds any stocks, bonds or mutual funds (a basket of more long-term investment products). Debtor households (households with significant outstanding debt) tend not to hold many, if any, investment products. In addition, investor households tend not to hold significant debt (beyond short-term credit card debt). Therefore, another reasonable statistic would be average mutual fund balance per investment holding household.

Continuing with the example, let’s say that the mutual fund marketer already has a collection of customers (investors of every stripe) in the target neighbourhood whose average mutual fund balance is $30,000 per household. The average mutual fund balance per investment holder in the neighbourhood is, say, $35,000. This means that either (a) the marketer’s clients have on average $5,000 in additional mutual fund holdings that can be targeted for conversion to the marketer’s firm, or (b) the marketer’s clients tend to have lower mutual fund balances than average investor households in the neighbourhood. If corollary evidence suggests that (a) is most likely true, the marketer can compare the findings of the average balance per mutual fund holding household and the findings of the average balance per investor household to determine whether the marketer’s customers tend to share only a portion of their mutual fund business with the marketer’s firm or whether the customers are likely using other firms for their mutual fund portfolio management.

Perhaps the best example of using a denominator that does not correspond to the balance numerator would be outstanding mortgage debt per real estate holding household. Remember that WealthScapes does not make a distinction between mortgages held on primary real estate versus mortgages held on other real estate. In many cases, the marketer will already have a collection of clients who own real estate and a household needs to hold real estate in order to have a mortgage. Therefore, assuming a constant response rate per household and a fixed cost of marketing to each household, the marketer for mortgage-related products would want to target those areas with high mortgage balances per real estate owner.

Let’s build a new example of a marketer selling life insurance. For now, let’s assume the demographics of the population are homogenous (so there is no higher premium for older household maintainers, for instance) and further assume that the policy coverage is directly proportional to the outstanding mortgage debt, the premium is directly proportional to the policy coverage and the marginal profit is directly proportional to the premium. Because the marketer has the ability to directly target the homeowner subset of the population, the marketer would want to target outstanding debt via the homeowner and should target areas with high outstanding mortgage debt per real estate holding household. Obviously, if the marketer could identify the households that had mortgage debt beforehand (for example, when targeting a new “starter home” subdivision where mortgage propensities are quite high), it would be more appropriate to target areas with high outstanding mortgage debt per mortgage holding household.

The Right Denominator for the Right Job

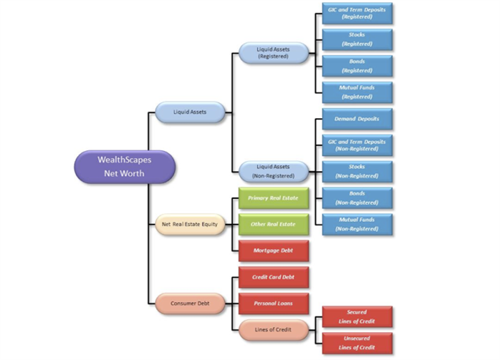

The aforementioned scenarios are by no means exhaustive. Great care has been taken in WealthScapes to produce robust denominators for all the levels of hierarchy of wealth. For example, in WealthScapes we provide aggregate GIC and term deposit balances despite offering the same aggregate balance (indirectly) as the sum of those GIC and term deposits in registered accounts and in non-registered accounts. However, the incidence for GIC and term deposit holdership cannot be reconstituted from the incidence of the registered and non-registered subcomponents available separately. Some households will own GIC and term deposits both within registered and non-registered accounts and would be counted once in the registered incidence, once in the non-registered incidence and only once in the total GIC and term deposit incidence. If one were to sum up all the incidences of holdership of the “end node” products (demand deposits, GIC and term deposits in registered accounts, GIC and term deposits in non-registered accounts, credit card debt, primary real estate, etc.) the sum would be well in excess of the total number of households in the neighbourhood due to the double counting. As a result, should the situation arise where one is interested in households that hold any stock or mutual fund, it is possible to derive the total aggregate balance of stock and mutual funds using the balances provided.

Once again, there are numerous ways to interpret any data and there are numerous scenarios, each requiring a different degree of finesse. Should you have any questions about which denominator is appropriate in your analysis, contact your Environics Analytics client advocate as we would be happy to be of assistance

# # #

Peter Miron is a Senior Research Associate, specializing in data mining, customer profiling, demographic forecasting, financial modelling, behavioural analysis and target marketing. The principal analyst for developing WealthScapes, he possesses a multidisciplinary background in quantitative economics, database development, spatial modelling and advanced statistical analysis. Peter also has broad industry experience, having conducted analytics in the automotive, banking, insurance, retail and travel sectors.

Peter Miron is a Senior Research Associate, specializing in data mining, customer profiling, demographic forecasting, financial modelling, behavioural analysis and target marketing. The principal analyst for developing WealthScapes, he possesses a multidisciplinary background in quantitative economics, database development, spatial modelling and advanced statistical analysis. Peter also has broad industry experience, having conducted analytics in the automotive, banking, insurance, retail and travel sectors.