There is Money on the Table

Challenges and opportunities of marketing to an older population

A silent shift is rapidly changing the demographic make-up of Canada. This change isn’t driven by external factors like immigration or refugees, it’s the result of Canada’s ballooning population over the age of 65.

As of 2016, there are more Canadians aged 65 and over than children under the age of 15. It is one of the most significant demographic trends facing the country today and it presents both opportunities and challenges to all organizations.

While governments have been preparing for this change, businesses have been slow to adapt. Rather than focusing on the older population, businesses generally concentrate their marketing and service efforts on the young Millennial population in their 20s and 30s.

Terry O’Reilly, host of the award-winning CBC Radio One/Sirius Satellite/WBEZ Chicago radio show, “Under the Influence,” captured the crux of this situation in his most recent book. “People over 55 have the most money and buy the most products. Yet, the advertising industry is infatuated with the 18 to 34-year-old target market,” he observes.

While this strategy may have made sense in the past, businesses that continue to fixate on the younger target market may miss a tremendous opportunity.

Boomer Spending Power

Historically, there was a good reason why businesses and marketers paid less attention to older Canadians: they represented a much smaller share of the total population and they typically had lower incomes. Part of that argument still rings true. According to Statistics Canada’s income estimates, persons aged 55 and over in 2016 had an average income of $43,000, compared to an average of $53,000 for persons aged 25 to 54.

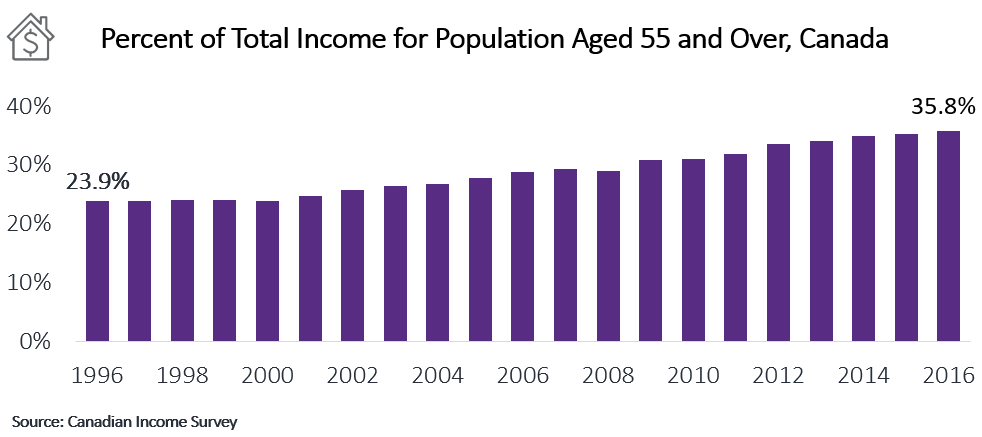

However, average income is only part of the story; the aggregate income of the older population is another important consideration. For instance, between 1996 and 2016, Canada's population aged 55 and over increased by 87 percent, whereas the population aged 16 to 54 rose by only 14 percent over the same period. As a result, even though income is lower at older ages, the combined income of the older population accounts for an increasing share of total income and therefore greater spending power. In 2016, the population aged 55 and over accounted for 36 percent of the total income, up from 24 percent two decades earlier.

Boomers Account for a Greater Share of Total Income

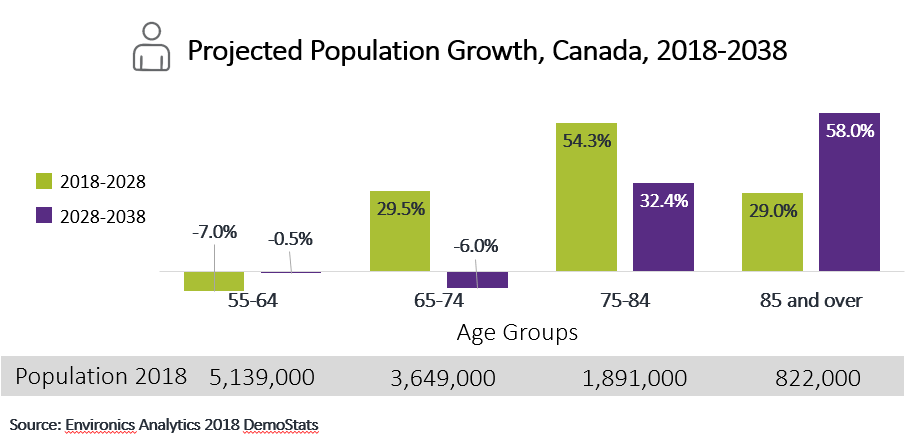

The already strong aggregate spending power of older Canadians will continue to grow. Over the next 10 years, Canada’s population aged 55 and over is projected to increase by 16 percent, while the younger demographic, aged 16 to 54, is expected to grow by three percent over the same period. Older Canadians have another advantage over the younger population: their accumulated wealth. With a lifetime of savings at their disposal, Canada's older population has a much larger average net worth, which can be a further source of spending power. The average net worth for households aged 65 and over was $845,600 in 2016, which represents an 86 percent increase from 1999, after adjusting for inflation.

Wealth Increases with Age

Characteristics of Canada’s Older Population

Demographically, Canada isn't just getting older; it’s becoming more female. While Canada's older population aged 55 and over is estimated to be close to 12 million, representing about 45 percent of all households, women already make-up more than half (52 percent) of this population. This figure goes up with age due to their higher life expectancy. Case in point: women currently account for nearly two-thirds of the population aged 85 and over.

The increasing diversity of the older population is another distinguishing characteristic of this generation. The cultural mix will also shift to include more seniors from continents other than Europe. Today’s older population has the highest percentage of foreign-born residents compared to the younger age groups, although most have been in Canada for more than 35 years. Unlike more recent immigrants, close to half were from Europe or the United States. Over the next 10 years, we will see increasing numbers from Asia and other parts of the world. Regardless of where they’re from, the older generation will also be even more highly educated. Half of Canada’s population aged 55 and over have a post-secondary degree or diploma and that figure will continue to increase.

Older Canadians today will also stand out from their parents’ generation due to their increasing vitality and life expectancy. Today, on average, a 65-year-old male can expect to live an additional 19.3 years and a 65-year-old female an additional 22.1 years, compared to 14.7 and 19.0 years in 1981, respectively. Canadians are not only living longer, they are also healthier, which means they can be more active in their senior years—and for a longer period—than their parents’ generation at the same age.

Unlike their parents’ generation, older women will have a different perspective on retirement, as they would have spent more time in the paid labour force than their mothers did, which also means they'll have higher incomes. Furthermore, more men and women are likely to remain in the labour force well past age 65.

The changing needs of the diverse older population

Whether you’re planning a marketing campaign or trying to improve the way you serve a particular segment in the market, it is essential to recognize the diversity within your target population. When looking at seniors, it's important to remember that this segment is made up of several distinct subgroups, which may have their own unique needs and preferences. In the case of Canada's older population, there are several different living arrangements, health statuses, employment statuses, lifestyles and other factors to consider. More importantly, these needs and preferences are heavily influenced by age. As a result, their daily activities and spending patterns vary, depending on which part of the older population you’re trying to reach.

As a starting point, it makes sense to break down the older population into separate age brackets. Older Canadians can be separated into four distinct age groups: pre-seniors, young seniors, mid-range seniors and older seniors. Understanding the preferences and challenges facing each of these groups will help organizations recognize opportunities—and there are many. Overall, spending data shows that the older population buys products and services in all categories, which suggests that all businesses will see increased demand from a growing older population.

Pre-seniors (ages 55 to 64)

More than 40 percent (5.1 million) of the population over 55 falls into the pre-senior category. Some older pre-seniors have transitioned to retirement; however, nearly two-thirds of this group continues to be active in the labour force. Most (71 percent) are living as a couple and 30 percent those households have older children living at home. At this stage of life, many are also engaged in caregiving for an elderly parent or other relative or friend.

This group has relatively high household spending rates, although they are spending less than the mid-age group (30 to 54). Most of the pre-seniors are in good health. Their spending patterns will be very dependent on life stage (employed vs. retired and/or the presence of children at home). Some of the areas where there may be opportunities include the following:

- Although relatively healthy, pre-seniors will likely spend more on health products and services, such as hearing aids or eyewear, as well as prescription drugs related to chronic conditions.

- This group will likely have a higher need for financial services, primarily as they relate to planning for retirement.

- There will be increasing pressures on pre-seniors to provide care. As families have become smaller, it means the number of potential family caregivers has also be reduced. Families are also much more complex and geographically spread out, which will add to those pressures.

- Empty-nest couples will have more discretionary income.

- Retired pre-seniors will begin to look at more leisure time activities.

There is one other factor that will set pre-seniors apart from other older Canadians: their numbers will decline over the next few decades. Although this group represents the largest slice of the 55-and-older population, they represent the last of the Boomer generation. In the coming years, the leading cohorts of the smaller Gen X generation will enter the pre-seniors segment.

Canada’s Uneven Population Growth

Younger seniors (ages 65 to 74)

While the number of pre-seniors is expected to decline in the coming years, the number of younger seniors is poised to grow. As of 2018, this group was estimated to number 3.6 million, but it will increase by nearly 30 percent over the next decade. Most Canadians who make up this cohort are still in relatively good health, with only about one in eight requiring help due to a long-term health condition. Caregiving remains a common activity for this group. Even with a trend towards delayed retirement, the majority of this cohort are retired. One in five is still employed, although most of those people are working on a part-time or part-year basis, with a large number being self-employed. Most in this cohort (70 percent) continue to live as a couple, many of whom are empty nesters, with only one in 10 couples having a child still at home. Opportunities for businesses include:

- Younger seniors will increase their spending on health-related products.

- This group will require more financial advice on managing pension assets as RRSPs must be converted to RIFs at age 71.

- Young seniors who may have delayed travel will begin to plan more trip. As such, the demand for travel advice and, particularly, packaged and/or adventure trips, will likely increase.

- For those with higher incomes, sports cars and other recreational vehicles may attract attention, as Boomers seek to remain young.

- Likewise, legalized cannabis may take many back to their younger years.

- At this stage of life, many will start to consider a residential move to a condominium or adults-only community that is close to amenities. This may also increase demand for new furniture and household appliances.

- For those who decide to remain in their homes, they may consider renovations, which could include making changes to make the homes more accessible.

- Innovative homebuilders can show leadership in developing new housing alternatives that allow the older population to age in place and remain in their communities where they can be close to family and friends. This is a particular challenge in the suburbs, where young families have long been the focus.

Mid-age seniors (age 75 to 84)

While the population of mid-age seniors numbered 1.9 million in 2018, it is expected to increase by 50 percent in the next decade, followed by an additional 30 percent growth in the following decade. Typically, as Canadians reach their late 70s, health issues become more common and they need more help with daily activities. As a result, this is the age bracket when some seniors will start to transition to a retirement or nursing home, with approximately seven percent of this cohort doing so. More than 55 percent of seniors aged 75 to 84 are women. Many of these women are also living alone. Almost 40 percent of women live on their own, compared to just 18 percent of men. Homeownership begins to drop for this age group, and there is a shift for both owners and renters to high-rise apartment living. Opportunities include:

- Many in this group are still in relatively good health, but spending on health products and services will continue to increase.

- Travel services will continue to be in demand.

- Mid-age seniors will still consider moving, especially following the death of a spouse or partner. In some cases, they may decide to sell the family home and move to a rental apartment.

- Retirement homes may start to become attractive to some members of this cohort, while others may require the additional level of support offered by nursing homes.

- For those who age in a community setting, there will be an increased need for home care and services.

- In this group, there are many more women living on their own and their need for products and services will change. Smaller packaging and home delivery may be much more in demand.

- Suburban living may become more difficult; if driving is no longer an option, this may present opportunities for new transportation options.

Oldest seniors (85 and over)

This group was estimated to be 822,000 in 2018, but is projected to increase by 29 percent over the next decade and 58 percent the following decade. Women account for two-thirds of this age bracket. At this stage in life, mobility and other health limitations become more common. Over a third (37 percent) of women and 24 percent of men aged 85 and over are living in a retirement or nursing home. Of those still living outside of retirement or nursing home, half of women live alone. By comparison, just over one in four men in this age bracket live on their own. For many people in this group, health status becomes more of an issue, although many older seniors are still quite independent. Opportunities include:

- The demand for senior residences and nursing homes will significantly increase, but a major challenge will be finding appropriate and affordable housing for lower-income seniors. An example of a particularly innovative approach that allows seniors to age in the community is the Oasis Project in Kingston, Ont. This provides supportive living in existing apartment buildings where there is a naturally occurring retirement community.

- Those who age in their own homes will also have an increased need for home care and services.

- Those who no longer drive will need access to both goods and services. Technology offers great potential in this regard with the development of autonomous vehicles, home monitoring devices, online purchasing of groceries and many other services.

- Finally, caregiving is an important issue for this population and there will be a greatly increased demand for such services.

How to Market to and Serve Older Consumers Better

So what do older consumers want? A recent study by the Global Business Policy Council attempted to address this question: “On the whole, mature consumers want and expect a sympathetic understanding of the realities of age, but they do not want to be treated as old or elderly.” So what can businesses do?

First, it is important to recognize the opportunities presented by a rapidly growing older population. The stereotype that the older population is set in their ways, not interested in new products, are very price sensitive and unlikely to switch brands must also be rejected. More advertising needs to be directed at the older population showing them as interested, active and open to change.

Some businesses offer seniors discounts or special senior days. At the same time, businesses need to recognize the reality of increasing health and mobility limitations, especially at older ages. Consumer research identified problems for older consumers including the inability to navigate large stores, products that are too many hard to reach, labels that are difficult to read and products that are difficult to open.

Retailers may want to set aside shelves or aisles devoted to certain types of products that are more relevant to an older population. They may also want to look for ways to make their stores more accessible, by introducing wider entrances, aisle and bathrooms, or offering motorized scooters to their older shoppers. Many would also appreciate a bench or chair to sit and rest throughout the store. This is particularly relevant to local, main-street businesses. The ability to get to retail space, accessible entrances and walkable neighbourhoods will push local business improvement areas to address this growing market.

Second, the Boomer population will demand good customer service. The string of automated phone instructions that annoyed Boomers will be a thing of the past. Use of smartphones can no doubt help with communications. Training of retail staff must address the age-related changes, overcoming stereotypes of older consumers and practical solutions to improve customer service, communication and accessibility of retail and online environments.

Third, the older population may also provide businesses with opportunities to develop or promote new or different products. An example of where a focus on the older population was successfully implemented is the Gillette Company. Gillette recognized the importance of a freshly shaven face for many men, but also acknowledged that, due to illness, some men could no longer shave. The solution was Gillette’s new TREO, the first razor engineered for caregivers to shave men who are unable to do so themselves.

In some cases, small, easy-to-implement changes may be welcomed. For example, in new condo sales, especially those targeted at the older population, offering a package that makes the new home more age-friendly (e.g., wider doors, grab bars, monitoring system) might be attractive to new buyers, including younger ones that may have older family members visiting. Another example of a small, but helpful, change can be implemented when advertising tours or cruise packages. Vendors can include more detail around the amount of walking involved in various side trips.

Fourth, the Internet and social media are increasingly used for marketing and online shopping. While today’s older population is less connected to the Internet, more than 60 percent of persons aged 65 to 74 use the Internet daily; this will continue to increase as younger cohorts move into the older age brackets.

Social-media use is rapidly increasing amongst seniors and should be part of marketing strategies targeting this demographic, but it requires a different approach from the one used to appeal to Millennials. Facebook is a favorite of many seniors, while Instagram is used much less. It is also important to recognize that language use may differ between seniors and younger generations. Jargon and Internet short forms that are cool common with young people may not be understood or used by an older consumer. Online shopping for groceries, meals and other products, perhaps coupled with home delivery, may be attractive for many seniors. Similarly, while seniors aren’t seen as embracing technology as much as younger consumers, they may be drawn to wearables and apps that help with healthy aging.

Finally, although the older population purchases goods and services for themselves, they also spend on aging parents, children and grandchildren. Nearly a third of the older population are caregivers, caring for other family members due to age-related changes and disabilities. As a result, many will have out-of-pocket expenses related to transportation, travel, accommodation, health services and medication. Nearly three-quarters of Canada’s seniors have grandchildren. Some toy stores have begun to recognize this and offer discounts to grandparents one day a month.

Locating the older population

This paper has pointed to the opportunities for marketing to Canada’s older population. As with any characteristic, neighbourhoods in Canada vary widely in terms of the size and concentration of the older population. Organizations will need to be able to locate these neighbourhoods to implement an effective marketing plan.

A simple approach is to use demographic data to identify neighbourhoods of interest. For example, in 2018, it is estimated that 45 percent of all neighbourhoods (dissemination areas) in Canada had a majority of the 55-and-over households. In some cases, these neighbourhoods overwhelmingly consist of seniors; there were 3,550 neighbourhoods in Canada where more than 70 percent of households are aged 55 and over. These neighbourhoods could be further segmented by size or by income, ethnicity or any other characteristic of interest.

An alternative approach is to use a segmentation system, such as PRIZM. Of the 68 PRIZM segments, 30 have a majority of older households. The oldest segment is Grey Pride, with 72 percent of households over the age of 55. Grey pride is home to well-educated singles, widows and widowers who are mostly living in apartments in the large urban areas. The average income for this segment in 2018 was $92,600. They are discriminating consumers who only buy what they think is useful and take the time to research a product before making purchasing.

Another segment with high penetration of older Canadians is Heartland Retirees. Two-thirds of all households in this segment are aged 55 or older. These households are widely scattered across rural Canada and enjoy their rural ways. They have an average income of $84,300, which is relatively high for rural areas. They are less likely to define themselves by material possessions. To them, shopping is on an “as-needed” basis and they want products and services that fit their lifestyle and come from companies that are responsible and ethical.

Canada’s older population is the fastest growing age group and this will continue for the next several decades. Within the next 20 years, the older population, aged 55 and over, will account for almost a quarter of the total population and nearly half of all households. The size and wealth of Canada’s older population mean that they have considerable spending power and this will further increase over the next several decades.

These seniors will have very different needs from younger consumers. Businesses need to recognize this and may need to modify their products, services and even their retail environments to serve the older population more effectively. In many cases, the modifications may not require much effort, but they could go a long way to retaining the older population as clients.

It is also important to recognize that the older population is a very diverse group and segmentation is an important tool in reaching the target group of interest. Even a simple segmentation by age group can be useful, although much more sophisticated segmentation schemes are possible. An AT Kearney report summarized the advantage of an age-friendly business as follows: “By providing the retail spaces and products that can help meet the needs of aging consumers, our members can create an immediate impact and a long-term advantage not just for our industry, but also for society as a whole.”

Doug Norris, Ph.D., is a Senior Vice President and Chief Demographer at Environics Analytics and one of Canada’s leading experts on the census.